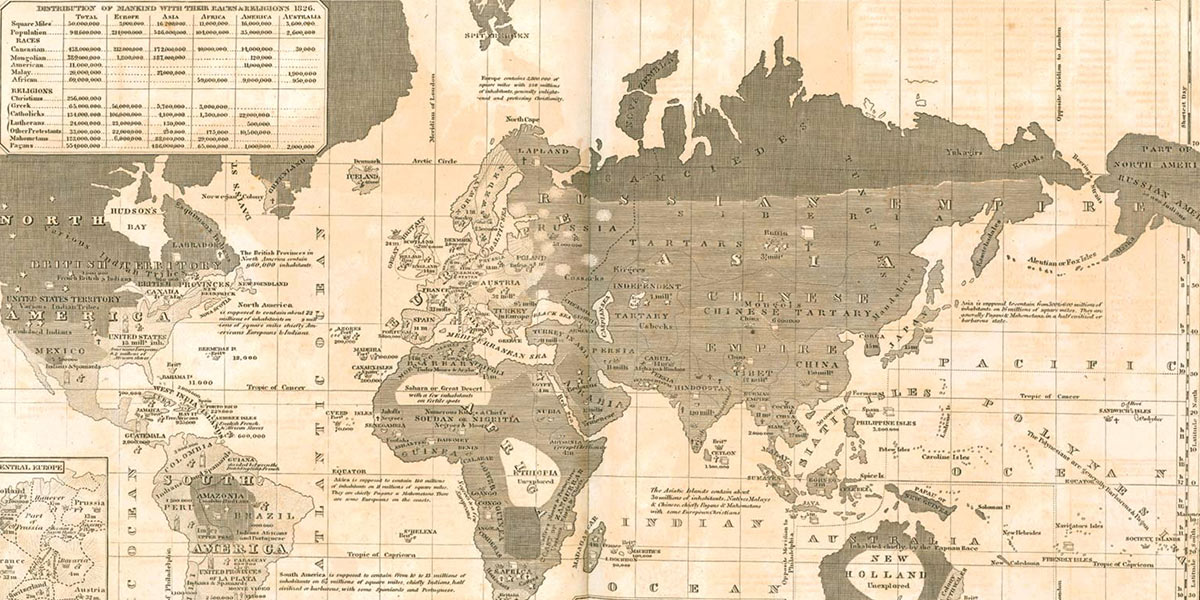

The defining concepts of modern political life, such as freedom, equality, democracy, justice, representation, culture, equality, the citizen, the nation-state, majority and minority, are all concepts taken to often be transparent and normatively the marker of progress, and the product of Western civilization.

In short, the dominant aspiration is towards what we call liberal democracy and its political subject – the rational autonomous individual. More democratic versions of our political modernity are emerging in the realms of history, sociology, and anthropology, to suggest two propositions that challenge this origins story- that the Western tradition is the product of borrowing from other traditions, and secondly, that political modernity itself might not be singular but rather plural. In this view China, South and Southeast Asia, Latin America, and the Middle East, contain within them histories of intellectual life that have produced knowledge which has contended with the major predicaments of contemporary political life. How will we bring into our education, as educators, and scholars, these debates, and bodies of work? How will we grapple with linguistic divides that require the work of translation? We are already aware that a rich history of political thought that resides in the reflections of Africans are in many instances not yet adequately a part of our curricula- the work of scholars like Houtondji, Wiredu, Diop, and anti-colonial thinkers like Fanon, and Cabral, to Nkrumah, Molema, and Nyerere, and political theorists like Peter Ekeh and Claude Ake. What are the implications of these propositions for how we teach political theory in our times? By this we mean, in contrast to the way in which this question was posed in the immediate moment after colonialism, when justice meant one form of centrism might have been replaced by another, when to Africanize the curriculum was interpreted as displacing the European canon. Rather, how do we navigate towards a pedagogy and a curriculum which grapples with political philosophy and political theory as a diverse set of intellectual traditions which are neither discreet nor static but rather entwined and dynamic?

With support from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, these are some of the questions that the Citizenship and Justice initiative core to Political Theory and Philosophy explores through reading workshops, fellowships, seminars, and colloquiums. The convening committee of the project comprises of Suren Pillay (Principal Investigator, CHR), Laurence Piper, Cherrel Africa, Ayanda Nombila (Dept. of Political Studies), and Tony Oyowe and Ryan Nefdt from the Department of Philosophy at UWC.

Political Theory and Philosophy intersects with two main CHR research platforms: Becoming Technical of the Human and Migrating Violence.