A report, crafted by Lee Walters, 31 July 2025

We said in our introduction that man was an affirmation. We shall never stop repeating it. Yes to life. Yes to love. Yes to generosity. But man is also a negation. No to man’s contempt. No to the indignity of man. To the exploitation of man. To the massacre of what is most human in man: freedom.

Frantz Fanon, 1952, 1960

The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.

Audre Lorde, 1979

In the back of my mind there is the scene where a whole village is the band, and each contributes what he can–there is never an objective audience–it is a matter more of inspiration and quite heavy common heritages… In a way what I’m doing with the Brotherhood of Breath is forming my own village… We snatch things from circumstance.

Chris McGregor, 1971

In anticipation of the arrival of Fanon, Lorde, McGregor and several other truth-seekers, the Iyatsiba Lab, alive to its meaning “to jump”, called attention to the CHR’s 15th iteration of the annual Winter School titled Freedom, Techne/Technics, Postcoloniality. Accompanied by trusted companions, the Reading List, the Place/People, Concept and Programme, Winter School held interdisciplinary space for what it means to think and make in relation(s) at the edge of time. This undertaking unapologetically cultivated thought practice(s) open to provocation and responsive to learning how to learn. In its commitment to understand the implications and consequences of theory, public discourse, art and the role of the university today, Winter School across the Iyatsiba Lab, the Slave Lodge, Zeitz Mocaa Museum of African Contemporary Art and UWC’s Main Campus did not disappoint.

In Another Freedom: The Alternative History of an Idea, Svetlana Boym draws attention to technê as a concept to think with/on the question of freedom. Technê unlike “mania” (derived from “madness and inspiration”) in Greek tragedy, referred to crafts, skills, and arts as key to doing the work of freedom.[i] This distinction between mania and technê, Boym explains, found further translation into what, for the Greeks, distinguished liberation from freedom. Liberation, here, is inspired and relatively short lived. Freedom, very differently, is concerned with an approach to aesthetic judgement and judgement, generally. This, Boym continues, is an enduring process that requires an agreeable environment for the cultivation of freedom as the capacity to judge, to discern.

Now, technically, that’s fine. The problem however is how attachments to that formulation, to how freedom is cultivated in the context of ancient Greece, elides the lives and histories of actors at play in the story of this year’s Winter School. That freedom as we shall observe fails to acknowledge Sara’s humanity or her suicide.[ii] What her death in 17th century Dutch rule at the Cape would mean for slaves in the aftermath of Slavery at no point figures in ancient Greece. Freedom, there, translated as naturalized legal or social entitlement that disavowed Sara. Where, for instance, might the notion “Africanity” – as championed in the work at Zeitz Mocaa – stand in relation to Western philosophical discourse, particularly if Africanity’s intention is to free art in Africa from empire’s grip on art’s history and markets today?

Though important and useful, freedom in Western thought traditions also fails creative destruction as an improvisatory principle in free jazz, as it does creative reasoning as embellishment and strategy in Black or Subaltern intellectual traditions. These possibilities of knowing, of making knowledge, and playing freedom have – on terms we associate with the truth-seekers who opened the present introduction – demonstrated a conscious aliveness to subaltern subjectivity, and to what being black in the world might or might not mean. Crucially, they rely on ways of thinking and making whose practice is to always question.

In this year’s programme scholars and students from UWC/CHR and partner organisations, including the Institute of the Humanities and Global Cultures (IHGC) at the University of Virginia, the Interdisciplinary Centre for Global Change at the University of Minnesota (ICGC) and global:disconnect at Ludwig Maxmillian University convened from 7th-11th July. For the first time, Chepape Makgato, Chief Curator at William Humphrey’s Museum in Kimberly also represented Sol Plaatje University and Monika Mehta, currently based at New York State’s Binghampton University, joined the annual gathering.

Attuned to shifts and scales in epochal and historical time, the 15th iteration punctuated scholarly and aesthetic practices in ways open to times’ remixes. The combination of contributions to Winter School consistently returned to what it might mean to remake, reclaim, rework or re-future involvement in the recalibration of critical approaches to the question of freedom? A freedom free of/from domination, if you will. Significantly, then, a sensibility to/of care prevailed. The conviviality, hospitality and daily rituals, such as, what it means to hold another’s thought or to break bread together communicated Iyatsiba’s waystation quality. In the face of unprecedented precariousness, scholasticide, and all sorts of crackdown operations in education’s current climate, globally, that gift of intellectual sanctuary can be conceived as priceless.

With each session, participants were encouraged to think through, to make with and against the constraints of the current conjuncture, marked by the effects of ideological stasis and unprecedented technological innovation. To therefore think any possibility of freedom – at once tethered to its postcolonial moorings and postapartheid provenance – meant staying – albeit sometimes awkwardly so – with a composite problem: race, sex/gender, and the myriad implications and consequences of those dynamics under capitalism today; this included questions about their co-constitution and specificity, in what, for this report’s purpose, I name third and fourth world non-place(s). Non-place(s) here acts as shorthand to describe transhemispheric relations in material and immaterial articulations in/of life, people and cultural worlds whose becoming-minor in the Deleuzian sense moves thought and practice to a freedom for a majority world.

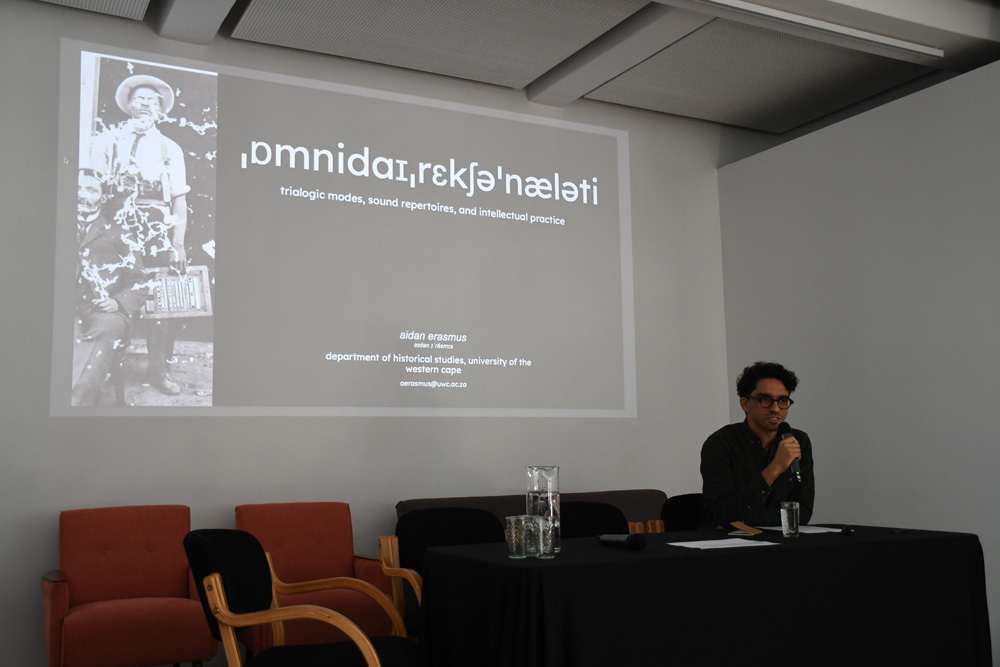

Winter School’s conceptual refrain engaged what becomes of freedom when free acceptance of law both frees and subjects formation(s) and interpretation(s) of a world’s majority to a time dominated by multiple crises: genocide, racism, war, femicide, scholasticide, ecocide, poverty, techno-positivism or neo-fascism to name a few. To think the role and function of freedom in the world and why freedom as a question remains necessary for Winter School is suitably exemplified by what Erasmus, in his lecture on Sol Plaatje named an “omnidirectional” quality. Borrowed here, it means to lean in, to listen, to touch, to respond to, to observe, embody, speculate and make ambiguous any received notion about a practice, question or answer of/to freedom. It also means philosophical, aesthetic and political praxis attend to an ongoing /emergent dialectic in the relation between law and freedom.

Four prompts activated the week long’s provocations: What are the stakes of a concept of freedom for the humanities today; How do technological constraints limit the possibility of such concepts; What is left of postcolonial concepts of freedom; and, Is “freedom without handrails” possible? Facilitated by Jack Chen, Ajay Skaria, Maurits van Bever Donker, Ciraj Rassool, Heidi Grunebaum, Premesh Lalu, Patricia Hayes, Rui Assubuiji, Reza Khota, Lee Walters, Geraldine Frieslaar, Simone Momple, Ben Verghese, Valmont Layne, Sam Longford, as well as Phokeng Setai and Beata America at the Zeitz Mocaa, the programme comprised student roundtables, extended lectures, short provocations and lengthy discussions, as well as museum talks and walkabouts, including:

- Federico Cuatlacuatl (2025). Smuggling as Resistance – Transborder Nuhua Futurisms.

- Lindelwa Dalamba (2025). Kongi’s Harvest: Jazz, Myths and Rituals of a Postcolonial World.

- Aidan Erasmus (2025). Omnidirectionality: trialogic modes, sound repertoires, and intellectual practice.

- Geraldine Frieslaar and Patricia Hayes (2025). Inside the Mayibuye Archive and Art Store.

- Kim Gurney (2025). Future Forms.

- Bongani Kona (2025). Spaceman. A Short Story.

- Sam Longford (2025). Entangled Freedoms, macro-history and the walking archive.

- Premesh Lalu (2025; 2000). A visit to the Slave Lodge, Cape Town; and an article “Sara’s Suicide: History and the Representational Limit”.

- Valmont Layne (2025). Vocal Individuation and the Relation between Sound Recording and Writing.

- Marcos Martins (2025). Facts and Fabulations.

- Monika Mehta (2025). Censorship 2.0 – Hindu Nationalism and Media in Digital India.

- Phokeng Setai and Beata America (2025) Walking Contemporary African Art inside Zeitz Mocaa Museum.

- Shelby Sinclair (2025). Race, Gender, and the Meaning of Freedom in U.S. Occupied Haiti 1915-1934.

- Maurits Van Bever Donker (2025). Freedom, Technically.

- Ben Verghese et al (2025; 2023). A Sonic Excursion / Practice across UWC’s Campus.

- Lee Walters (2025). Organic Feminism, the Art of Knowing and the Crises of Postapartheid Patriarchy: Cultural Workers’ Perspectives.

- Lisa Woolfolk (2025). Black Women Stitch Liberation: How Freedom is Fed with Needle and Thread.

In what follows, and before any final impressions, this report continues with a rough take Inside Winter School’s Poetics: To Rap/Unwrap Freedom before the sections Setting the Record Straight and Walking, Experiments and Augmented Reality, track thematic prompts, movements, questions and conceptual insights put forward by faculty and students.

Inside Winter School’s Poetics: To Rap/Unwrap Freedom

How might we orient thought practice as an art of/for freedom when often what we sense is devastatingly venomous? A hiss, if you will. Why, how or what might this hiss signify? Sara’s suicide, perhaps. Maybe, Ogun’s remedy? Might it [the hiss] also sound freedom? In which case, it can conjure women’s strident steps, imaged in the 1930 march to Black freedom (Sinclair). But, is this a forgotten freedom that (today) haunts Haiti, remembered only for its future – when boots on the march smothered snake sounds?

Yes, Hani’s boots! Lest we forget their fabulated style, their mark when meaning confronted nocturnal evil (Longford). I imagine Hani’s shuffle through the bush, now reassembled by Moholo’s brushstrokes as he reworks sound in the Brotherhood of Breath. Soon afterwards, both Hani and the band free (jazz) from imperial confinement. Hani, to be sure, paid the ultimate price. And the Brotherhood unleashed creative destruction. This as a matter of principle, improvised (Dalamba). By the time it reached Plaatje, the element of destruction had come full circle. What we hear here are phonetic explosions.

Remember, Plaatje moved phonetically. He shuffled between translation and transcription (Erasmus). In Plaatje, a liberal hiss seems to question and refuse Roman-Dutch Law’s contempt for African people. His sharp, creative reasoning tracked South Africa’s upheavals and courtroom dramas in late 19th – early 20th century. Inside the courtroom, Plaatje’s three-step staccato translation, labour, and love secretly infused hope into the souls of the country’s black folk. For Plaatje, interpretation mediated freedom. For us, his people, interpretation apprehended an extended, phonographic arc of a trialogue to come: Judge-defendant-Plaatje; Defendant-Plaatje-Judge. Plaatje-Defendant; Whispers-Murmurs-Order; Defendant-Plaatje. Judge. Plaatje. Stop.

Years later, it is Nokhupila, Sara’s great-great-grand offspring and her friends who in State v Mthethwa loosen colonial patriarchy’s legal grip. The moment Black women’s bodies glowed in this light art of knowing, word about Sara’s and Nokhupila’s freedom went viral (Walters). In the meantime, the hand in Black women’s movement guided needle and thread. The stitch in this rhyme gestured to truth’s future, generosity and time. No doubt, here too, creative reasoning embellished freedom as practice and, gracefully, inventive technologies shaped the eye (Woolfolk). When that very same movement rubbished the imperial divide it dealt The Genuine(s) a knowing hand. In this collective seam, freedom moved into a punk accented free jazz and lush sound for keeps (Layne). Freedom. Embodied. Crafted here, elsewhere. Always already there.

But, did the turkey take a Panya route to the land of the free? (Gurney). Into the heart of Mexico: elsewhere, always already there? (Cuatlacuatl). And, what became of Chimurenga’s Afronauts? Did they leave the dog behind? (Kona). Will they meet again – in this, our off time? One wonders. On that beautiful island along the coast of Spain, perhaps – where in the fight against new old nationalisms, fascisms and big men, the digital’s brilliant light arms scandalous resistance, rebellion and revolution. Oh, dear India, you are loved; you love, remember (Mehta).

Meanwhile, a distinctive chant “Hek toe” portends freedom, and cuts into the still air at Udubs (Verghese et al.). A bush campus about to erupt. Unwittingly, perhaps not, the phrase sculpts forms of memory-becoming: sonic, embodied, tactile, visual. And some decades later an archive is born. Protected, in fact and future’s fabulations (Martins). To “Mayibuye”, the students respond “iAfrika”. And on the liberatory line, “Hek toe! Hek toe!” freedom’s echo bleeds into the in-between: struggle lived becomes struggle continued: forever, elsewhere, always already there.

Thankfully, Freedom’s children are in class and The Herds are en route to the Arctic Circle.

But important considerations remain. Might becoming-Sara, in the wake of freedom’s tragedy, mean setting the record straight? (Lalu). Perhaps, Freedom, technically, implies recognition of freedom’s conditioned other(s): apartheid’s inglorious scale in a cruel global postcolony. Of a type Fanon alerted us to? (Van Bever Donker). It’s plausible. Suggestively, then, authentic movement to the fact of freedom’s impermanence, in history’s non-place(s) invites and propels invention. Along the detours, routes and roundabouts, and hisses sketched here, winter school connected variations on the concept freedom.

Setting the Record Straight

While the title to this section is inspired by the absurd hubris I imagine accompanied the act of writing a colonial record, it is ‘Sara’s Suicide: History and the Representational Limit’ that helped frame Lalu’s lecture at the Slave Lodge. To consciously set aside colonialism’s claim to case law and criminality, Lalu’s translation of Sara’s death and untold truths surrounding her death makes for a different reading of the tragedy. This way immediately diminishes The Colonial Record’s hegemonic force in the translation of history. With Lalu’s assistance it is Sara who sets the record straight. This return to Sara’s death, coupled with the Slave Lodge exhibition prompted Winter School participants to question political, economic and social dynamics that currently play out in today’s post-imperial world.

For instance, how might we connect dangerous conditions faced by people forced into migration to the sheer will of technological domination and ongoing atrocities of genocides and war? What do these point to? Might it signal capital’s recalibration, to put in place and reassemble forms of slavery that enable extraction and consumption today? Might clearing vast tracks of lands and countries point to an imminent erection of high speed data warehouses? All this to advance communication? How then might a thought or practice concerned with freedom interface with what today appears as a catastrophic moment for democracy the world over.

Freedom, Van Bever Donker reminded, necessarily develops a “critical posture that sets to work in the wake of slavery, ontologies of race and gender, and other violences, like apartheid, that have produced the State and the state of our conjuncture.” In other words, freedom cannot suffer. To live, freedom must jettison blind construction, and the application of cold rule, and law. That approach to freedom, as Lalu (2000) suggests, for history, and historiography becomes a practice grounded in the desire to set the record straight. Sara as fragment found, but not left for dead in 17th century colonial history at the Cape, aptly demonstrated the debauched arrogance of legality to emerge from Roman Dutch Law. This law’s hegemonic force, Lalu reminded, drove imperial expansion. It created political infrastructures, institutional mechanisms and social conditions that necessitated the reproduction of slavery.

To therefore pay attention to technological inventions, such as electricity, or shifts in communications, including transport, maritime, phonography, photography, cybernetic computation and, critically, the ordering of archives also means attending to how each advancement – and their technological network – supports or negates possibilities of freedom. If I understood Lalu correctly, an inquiry into how technology might reproduce regime(s) of material and immaterial labour that rely on slave bodies for the extraction of sensorial responses to technologies, might mean having to reformulate theoretical questions about how race, and racism, as questions are reassembled in the service of capital accumulation. Save to say my arrival at the concept “immaterial labour” is routed through works by Gill et al.,[iii] Lazzarato,[iv] Mbembe,[v] Todorov,[vi] and Williams,[vii] who in different ways raise questions about informational and cultural content inherent to the commodity form and the ideological underpinnings of their production. To quote Williams:

Our whole way of life, from the shape of our communities to the organization and content of education, and from the structure of the family to the status of art and entertainment, is being profoundly affected by the progress and interaction of democracy and industry, and by the extension of communications. This deeper cultural revolution is a large part of our most significant living experience, and is being interpreted and indeed fought out, in very complex ways, in the world of art and ideas. It is when we try to correlate change of this kind with the changes covered by the disciplines of politics, economics, and communications that we discover some of the most difficult but also some of the most human questions[viii].

Sara’s memory in the complex constellation of the current conjuncture helps recalibrate, or indeed fabulate, free responses to centuries of imperial and colonial violence. Her presence at Winter School helped open formidable and possible methods that aim to undo subjugation. For example, in the free jazz idiom, and with specific reference to the Brotherhood of Breath’s sound and time spent in Britain, perfecting an improvisatory method whose mbaqanqa rhythm section performed both accent and signature. This feature, insisted in the 1960s, affords today’s listener and historian to trace the music’s provenance. Dalamba demonstrated how the Brotherhood’s Afrological force at the edge of both Eurological laws in music and legality (as Black South Africans in exile, in Britain) consecrated the band’s inventiveness and contribution to free jazz in Britain.

If an absurd hubris accompanied colonial law, it remains Hindu nationalism’s self-regulation that evidenced a distinct form of hubris. In Mehta’s lecture, Censorship 2.0 Hindu nationalism’s prevailing fault lines pursue disconcerting levels of conservatism. Mehta illustrated how, in what should presumably circulate as an innocuous digital video display, pop love between a young woman and man did not escape India’s elite impulse to censor and censure. That the young woman was Hindu, and the man Muslim mattered plenty to the censoring eye. The music video’s popularity across digital platforms, coupled with the actors’ celebrity status increasingly exposed Hindu nationalism’s conservatism and its hostility to entertain any possibility of freedom.

This brittle configuration of conservatism, and its libertarian force bring acts of freedom into sharper relief. Black lives’ centrality to freedom as articulation (fullstop) is what informs liberatory practice at Woolfolk’s Black Women’s Stitch. For inspiration, and political practice, the collective practice turns to truth-seekers such as Lorde, and peers in the Black Liberation Tradition. Throughout, there is a turn to Africa – as method. Evidenced more so by the fact, as Woolfolk reported, the needle is an African invention. The collective’s work privileges “Human centred design”. This work of freedom operates as counter imaginary and force to standardized patterns. Indeed, it liberates the craft. And, both the craft and women involved activate and practice stitching moves at odds with ideologically imposed free market orthodoxy. With the needle’s eye and moving precision, Woolfolk and her folks organise apparels’ truth. In this time of Black lives’ negation. As Black Women’s Stitch “feeds sensibilities of freedom”, the simplicity of a moving hand, needle and thread threatens the tyranny of law.

In Cuatlacuatl’s smuggling act, the artist attends to subterranean articulations of freedom. He, his self, becomes a smuggled object, now entering a territory of ahistorical law obsessed with rendering criminal all and everything Mexican. That Cuatlacuatl risks visibility of his person/body and culture, vibrated with Fanon’s refusal of the script of Man invoked by Van Bever Donker:

Beginning from his body, from himself as his own foundation…he recognises and articulates the demand to question, to not accept the ideological productions that contain the world, but rather to invent new lines.

An engagement with Cuatlacuatl’s work necessitated understanding how neoliberalism’s free market desires effected trade treaties, and forced the artist, his family and millions more to migrate, from what they knew as home. To retain hope in the memory of home, and to create life in what feels unhomely in the United State, Cuatlacuatl’s digital and installation works play with Mexico’s landscapes and symbols. The works’ movements turn to (their) pasts and futures. The artist adopts sharp light, and effects brilliant colour to articulate a hope, a future. It is this, and the recreation of Mexican carnival that make up Cuatlacuatl’s arsenal, political assertion against domination and historical claim to the land, America. His emphasis, on epistemological, ontological, spiritual and juridical implications for Mexican culture in today’s United States of America entangle the materiality of land and culture with what appears as deep knowing – in and from a time before. This time eschews nostalgia. This time seeks out the workings of justice as a matter of principle.

Walking, Experiments and Augmented Realities

During the visit to Main Campus, participants took part in two activities, namely a sound walk through the campus and a visit to the Mayibuye Archives’ art store. Situating the sound walk, Ben Verghese, MA graduate in UWC’s Department of Historical Studies reported:

[…] developed in the African Critical Inquiry Programme workshop Archiving Otherwise: Sound Thinking and Sonic Practice, hosted at the CHR in 2023, the sound walk has become a New Archival Visions (NAV) output that has grown and shifted through half a dozen tryouts… Archived audio intermingled with sounds around us, including bird song and gqom… The sound walk began outside the CHR with an excerpt of Zoe Wicomb’s ‘A Clearing in the Bush’ read aloud… proceeded towards the Robert Sobukwe Road pedestrian entrance… and towards the old gate with cries of hek toe! Hek toe!

Similarly, but pointed to visual and tactile materiality, Winter School participants had an opportunity to engage the work of Buhle Ngada, a former CHR Artist in Residence. From Ngada’s reworked Mayibuye Archives’, she fabricated posters and placards and turned the archive into a space of play. In her work, Ngada draws attention to the connection between today’s women’s and youth struggles and those to be found as part of the liberation movement under Apartheid. As a final activity, participants entered Mayibuye’s AV digitisation room, the photographic collection, and historical papers.

Back at Iyatsiba, Marcos Martins, Bongani Kona and Kim Gurney explored different modes of archive mediation, and the experiments they afford. Gurney shared three provocations that shaped artists, and arts collectives’ modes of reinvention when faced by constraints embedded in unprecedented scales and speed of urbanisation across Africa’s cities. For example, a horizontal mode of operation remained central the work at Go Down Art Centre in Nairobi; Zoma Museum in Addis; Accra’s Anno Institute of Art and Knowledge; Town House Gallery in Cairo; and Nafasi Art Space in Dar es Salaam. That mode ensured a reciprocal mutuality between the collectives’ commitment to “shape shift” and use curatorial strategies inspired by and accountable to their surrounds, environment and reality. Gurney also shared technological innovations in digital video work by Russell Hlongwani, Francois Knutzer and Amy Wilson who develop artistic responses to environmental issues. And, finally, the idea “that every mark we make where every footstep we take carries our lived embodied experience with it” introduced Winter School participants to “Panya” routes. These routes are sympathetic to the everyday (of life), traversing local memory in ways that interfere with official statute or strategy.

Provisionally titled “facts and fabulations”, Martins’s work in progress, a curatorial project, aims to expand the reach of archival content and making in ways attractive to younger audiences and archive makers. The project would involve UWC students, and encourage “critical reflection” on what might be considered truth. In his demonstration, Martins’s experiment pushes the “truth of the image” to its artificially generated edge; and the use of AR technology makes available an “alternative experience” of truth. By selecting an image that initially draws one’s attention, and then setting aside the image’s archival inscription, a process of mixing images’ positive and negative properties commences the fabulation process – and consistently destablises the image’s “facts”. Anticipated for the project’s exhibition is how AR installed technology would radically slow down the speed of image consumption (synonymous with social media). The design of the interaction with digital media in reality would encourage a more deliberate engagement with the image, or a “more careful and detained engagement with visual documents typical of archival research”.

In Spaceman. A Short Story, Kona read from what he named “fragments’ from a story “inspired in part by Edward Makuka Nkoloso and the Zambian space programme as well the 1977 bombings of Chimoio in Mozambique by the Rhodesians”. In this fabulation, one can glimpse how the reworking of normative narrative associations can, if written from a future’s perspective, be attuned to the consequences of space programme and war, bring speculative historical narrations to bare. These narrations, akin to the work of Sara’s Suicide, and similar modes of reworking historical record, open onto the possibility of historically informed literary imagings and making.

If Martins’s fabulation aimed to destablise facts, Layne’s search for a method in Vocal Individuation and the Relation between Sound Recording and Writing alerted us to the challenge of aesthetic decisions. The aim of Layne’s process is to make sound sync with writing history and the moving image, in a way that brings his protagonist, Mac Mckenzie, a vocalist and guitarist, to the film’s interpretation of what free jazz and punk music attained for cultural liberation. To therefore think Mac and the art of freedom, from Cape Town into the world, Layne’s work pays homage to the uniqueness of McKenzie the artist and his contribution to freedom, and liberatory practice, at the edge of apartheid in the 1980s.

Sharing excerpts from the manuscript “Race, Gender, and the Meaning of Freedom in U.S. Occupied Haiti.”, Sinclair’s presentation turned to Haitian women’s lives, labour and political action during the 19-year U.S. military occupation of Haiti from 1915 to 1934. A map of the Caribbean, timeline of events, written archive records, and several images mediated Sinclair’s narration of the 1930s Liberty March – an event involving women, disavowed and disregarded in dominant narratives of Haiti’s history, and liberation. Indeed, the women’s action in that march enters into relation with Walters’s theoretical proposition “organic feminism”. This proposition, derived from a Deleuzian sense of “becoming-woman”, and an approach to culture and politics from the perspective Gramsci names “organic intellectual”- proceeds from the premise that the absence of a self-referential feminist identity in no way negates the movement and presence of a feminist sensibility. Sinclair’s study also found resonance in Longford’s presentation “Entangled Freedoms, macro-history and the walking archive” – in which one imagines what it might mean to walk with the object.

Albeit Hani’s Wankie Boots (Longford), the image of women on the march (Sinclair), or organic feminists’ lived experience as embodied knowledge, each presentation asked a question about what it might mean for (subaltern) subjectivities who– when faced with seemingly insurmountable obstacles – decide to move, in a/the movement to political freedom. By inserting micro-political perspectives or micro-historical objects and gestures into and against grand narrations, the subject/object relation in all three presentations aimed to glitch or, at the very least, make relational macro and micro instantiations of both history and politics.

Consequently, the question of method and the archive turned to how making history often necessitates an “authoring” process committed to the archive object’s vantage point and movement. This approach defamiliarises what, up until the objects insertion, shaped well-worn historical perspectives. For instance, the potential to disable nationalism’s hold over the narration of Hani the historical figure resides within and in following the object (believed or perceived to be) Hani’s Wankie Boots. The boots in other words afford entry to different accounts of Hani and his life as a communist, and freedom fighter. And the method, namely, to read and track the life of the object, not only reshuffles time but also avails multi-layered and multidirectional accounts of historical imagination and making.

[i] S. Boym, Another Freedom: The Alternative History of an Idea (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 16.

[ii] P. Lalu, ‘Sara’s suicide: History and the representational limit’. Kronos (89), 2000, 89-101.

[iii] R. Gill, M. Banks and S. Taylor, eds., Theorizing Cultural Work – Labour, Continuity and Change in the cultural and creative industries (London and New York: Routledge, 2017).

[iv] M. Lazzarato, ‘Neoliberalism in Action: Inequality, Insecurity and the Reconstitution of the Social’. Theory, Culture & Society 26(6), 2010, 109-133

[v] A. Mbembe, Brutalism (Johannesburg: Wits University Press, 2024).

[vi] T. Todorov, The Limits of Art – Two Essays (Calcutta: Seagull Books, 2010).

[vii] R. Williams, The Long Revolution (Middlesex: Penguin Books, 1965).

[viii] Ibid p.12